Dr Pat O'Hara

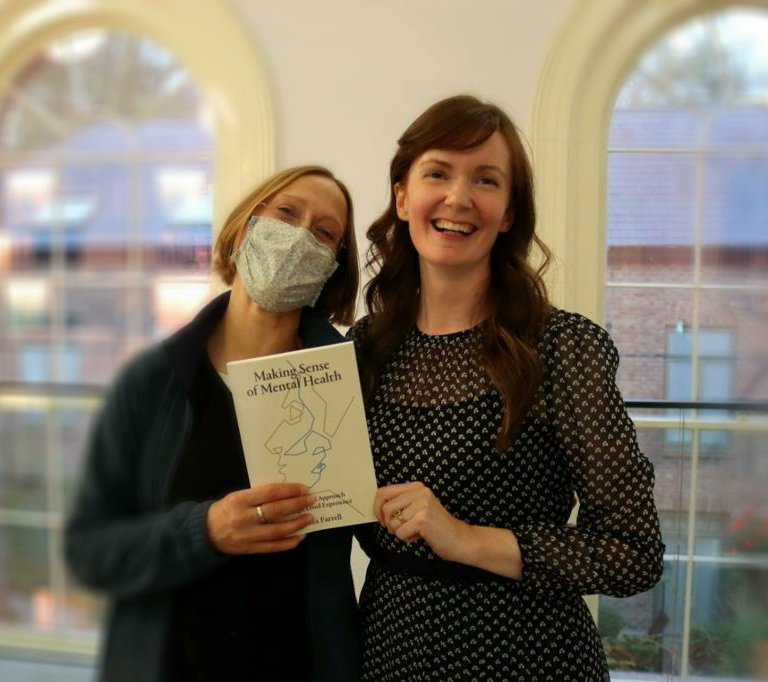

Good evening, you are all very welcome to the launch of Dr Emma Farrell’s book Making Sense of Mental Health.

My name is Pat O’Hara and Emma very kindly has asked me to be your host this evening.

As a former board member, and Chair, of Jigsaw, the National Centre for Youth Mental Health (formerly known as Headstrong), I met Emma when she joined the board in 2014. And as many of you will know, Emma was one of the founding members of Headstrong and by the time she joined the Board and I met her for the first time, she had begun her PhD studies at TCD.

Having trod the same path myself back in the day, I asked her about her dissertation. When she told me that she was going to research the lived experiences of people with mental health difficulties using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, I really had to steady myself!

As a sociologist, I could anticipate the difficulties of coming to terms with the challenging philosophical foundations of this approach that would be focused on meaning and understanding. And Emma would need to develop a methodology that would yield convincing and robust conclusions. On top of that, applying HP to such a sensitive subject matter – the complex and tangled nature of distress– to use Emma’s words, would be difficult and demanding.

My worry was that in a world dominated by positivism typical of the usual scientific approach (where the focus is on cause and explanation, rather than on meaning), Emma would be ‘going against the grain’ and might have difficulty convincing academic supervisors.

(By the way, if you wish to understand the difference between the dominant positivist and the interpretivist perspectives, I’d advise you to look at Table 1 on p.43 of the book where she contrasts them brilliantly).

But even though I was concerned for her, as I got to know Emma, I came to understand her courage, her empathy, and her fierce commitment to finding a way, as she herself puts it, to understand people’s experience of the world, rather than, as is more typical, quantifying and describing their experiencesin the world (p.53). So she persisted, found a way to do it and wrote a superb thesis which is methodologically rigorous and beautifully written, and which Trinity accepted without corrections. Of course, in the book, Emma had to leave out the detail of the distinctive methodology and analysis, which is at the core of what she did, but believe me, it is really impressive and robust, with every insight carefully calibrated.

To anyone reading her thesis, including her TCD Examiners, it was clear that she could make a valuable contribution to the discourse on mental health by sharing her research and insights with a wider audience. Meanwhile, Emma began working at UCD, moved to Stillorgan, and met and married the wonderful Shane Bergin her UCD colleague, a physicist, and Ireland’s finest science communicator! Covid and lockdown arrived, and to our great good fortune we live only two kilometres apart! So my husband Johnny Callaghan and I, became Emma and Shane’s Covid ‘bubblemates’ during the lockdowns, sharing many wonderful evenings of food, fun and discussion.

All the while, mental health became a bigger part of public concern and discourse, and more than ever, it was clear that Emma had something very important to say. She needed to be listened to beyond the confines of our respective dinner tables and other circles where she was publishing very well-received papers. A wider audience needed to hear and discuss her ideas and insights.

So began the journey that brings us here this evening to the launch of her book Making Sense of Mental Health. It has been a privilege to share a little of this journey with Emma, to read drafts and discuss edits and the all-important positioning of commas! And while few of you here will have yet read it, you can see from the endorsements at the front that it is enormously impressive. Emma writes beautifully and sensitively – whether in examining the history of how mental health has been understood through history, explaining Heidegger’s philosophy, or presenting the narratives of experience. Those who shared their stories with her were fortunate to have such a sensitive and painstaking researcher.

I’ll leave it to Emma to tell you about the book, but I can guarantee that you will find in it more than a few ‘That makes so much sense’ moments.

Professor Brendan Kelly

Brendan Kelly is my name and I am a psychiatrist and I'm really honoured and happy to be here at the launch of this wonderful book, which I have read. It is a beautiful venue, The Liffey Press are a fantastic publisher, I can't emphasise that enough, and it's an absolutely beautiful volume, as well as its content.

I want to say a few quick words about the book if I may. I appreciate the philosophical basis of it and the methodological rigour but, as far as I'm concerned, this is a book about conversations with a few dozen people about their experience of mental distress, psychological suffering, mental illness - whatever framework people use for that that makes sense to them. There is a lot of talk about this in the literature but there is the simple, irreducible fact of human suffering which I see everyday in my particular take on it as part of a mental health service. But its far far broader than that.

I just want to quote one or two things from the book that really gets to the heart of it. Emma writes"

"Humans are storytelling creatures who, individually and socially, lead storied lives. It is through the telling of stories that human experiences are made meaningful. In telling a story about an experience, either in our own minds or to others, we organise the experience into a meaningful episode or a 'whole'."

And that is so important because we have all struggled to make stories and make sense of what has happened during the pandemic, or in our own lives and we relate our present to our past and we build up these stories which are sometimes true, sometimes questionable but useful, important, in the way that we pattern things. I think this book is really really good, not only at giving the philosophical basis to understanding that but simply hearing that.

There are other things I really like and I'm just going to go for one other quote if I may. I'm a psychiatrist, I work in a hospital. The book has accounts of psychiatric hospitalisation, medication, diagnosis and lots of these difficult concepts that can be used well or used badly. I love this description of an inpatient psychiatry unit. This is from the book:

"Overall [one of the participants] described hospital as "a weird mixture of good and bad"."

Now, anyone who has had experience of psychiatric hospitals or psychiatric services will know that they are often a weird mixture of good and bad and at the risk of upsetting all my colleagues, psychiatrists are often a weird mixture of good and bad! but Emma is far too polite to say such a thing! Anyway, I just want to finish by saying the book is wonderful, it's important, it's considered, measured, it's balanced, it's readable, it's a beautifully produced volume from The Liffey Press. Congratulations again to Emma.

Dr Emma Farrell

It is a joy to stand here this evening and to share the launch of this book with so many friends and colleagues. After two years of being apart it is lovely to have an excuse to come together.

This book is almost ten years in the making although its origins go back even further than that to when, as an undergraduate student, I learned that one in four adults will experience a mental disorder in their lifetime. I became familiar with all the classic studies of human behaviour and learned when to select a t-test over a Mann Whitney U.

Yet, beyond my studies, I had the privilege, largely through my work with Headstrong, now Jigsaw, of listening to the rich and deeply nuanced stories of young people with lived experience of distress. These stories spoke of fear, disconnection, anger and shame, as well as strength, wisdom and indomitable courage. The young people offered insight into their unique and complex worlds in which symptoms made an awful lot of sense.

And yet, I struggled to find little more than snippets of these stories in the textbooks and academic journals that filled the college library.

This was, and in many ways still is, the problem that captured my imagination. Why is it that we place such little value on human stories and experience as form of information or evidence? And how can we capture the insights that lie within lived experience and use these to develop understanding, build policy and guide practice.

I was very fortunate to be offered the opportunity to study for a PhD with Professor Michael Shevlin, and later, with Dr Paula Flynn. Those three and a half years were truly a gift, and in addition to the freedom to devote all my time to this great intellectual challenge, I met and made so many wonderful colleagues and friends – many of whom are here tonight.

With this work, I wanted to demonstrate, not only how much we can learn from listening to the experiences of others, but just how valuable this form of knowledge can be.

In order to do that I needed to get as close as possible to the experience as it is lived, and to do so with the highest standard of methodological rigour and trustworthiness. The line between experience and anecdote is methodology.

That methodology was to come from the philosophy of hermeneutic phenomenology to which I was introduced though the work of Dr Pat Bracken who kindly wrote the forward to the book. Reading phenomenology, particularly the Heideggerian lineage, changed my life and how I see the world.

I also learned that telling people you are a hermeneutic phenomenologist is a sure fire way of finding yourself standing alone at a party so I won’t go into it too much.

What I will say is that I learned that the divide between experience and expertise will never be overcome by being more right. The mental health debate can be quite heated and polarised and contested, but it is only when we foster, to borrow that lovely phrase from Richard Kearney, “a hospitality of narratives”, where a range of perspectives are welcomed and considered respectfully, that we create the greatest potential for understanding. And I think that is what we all want - to understand and to be understood.

This book is an attempt to understand that experience of what we call mental illness. Disorder. Distress. The language itself points to just how ineffable this phenomenon can be. The one thing we can agree about these experiences is that they tend to be extremely distressing. They remind us of just how vulnerable we are as human beings - even beneath the veneer of modern comforts, advances and prosperity.

Most of all this book is a demonstration of just how much we can learn if we listen, without preconceptions or agendas, to the stories of those with lived experience.

I was so fortunate to meet 27 exceptional people, some of whom are here tonight, who so generosity shared their stories, their struggles, and how they made sense of them.

It is to those 27 that I offer my first and greatest thanks. Your dignity and willingness to share raw and often painful experiences in the hope that it might help somebody, someday, is a testament to the depths of your courage and compassion. I just hope I have done you justice.

Making Sense of Mental Health: A Practical Approach through Lived Experience is available for purchase from The Liffey Press, online and in all good bookshops.